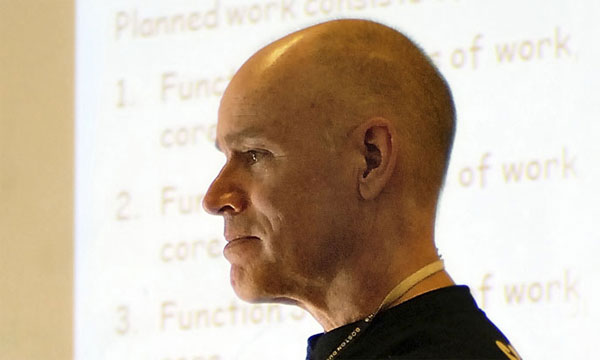

Ken Schwaber, who is known to be the co-founder of Scrum together with Jeff Sutherland, paid a visit to Sweden in April this year. Lean Magazine got a chance to talk with him about the origins and evolution of Scrum in the nineties, and what he thinks about the future of Agile Development.

Ken Schwaber, who is known to be the co-founder of Scrum together with Jeff Sutherland, paid a visit to Sweden in April this year. Lean Magazine got a chance to talk with him about the origins and evolution of Scrum in the nineties, and what he thinks about the future of Agile Development.Sutherland kept experimenting with his groundbreaking concept, which he had already started to call Scrum. Eagerly, he kept calling Schwaber for his advice on it. Sutherland wanted to compare Scrum to whatever process Schwaber was using.

“Jeff was under the impression that I was using one of the major methodologies, like Navigator, Method/1, or Summit. I told Jeff that I was using none of those, that I would have gone out of business if I relied on their unwieldy, unfriendly-to-change nature. When we compared what I did use with Jeff’s Scrum, they were very similar. The rest is history, as we collaborated to bring Scrum to life.”

The Evolution

Sutherland and Schwaber evolved Scrum through trial and error at a number of companies during the 1990s – NewsPage, IDX Systems, Fidelity Investments, and PatientKeeper. The Daily Scrum, the burndowns and the Sprint Backlog were added, and planning Sprints were dropped. The importance of self-managing, cross functional teams became apparent and a bedrock to Scrum.

Schwaber also collaborated with process control scientists at DuPont to tie Scrum to first principles in industrial process control theory, learning that the reason Scrum worked was that it was empirical.

“In 2001, the Agile Manifesto was formed,” says Schwaber. “The signatories gathered in SnowBird because we felt our approach to software development had something in common that was far bet- ter and more people-oriented than the emerging favored process of the day, Rational Unified Process. The principles of the manifesto are the common touch points that we agreed upon.”

Today, Schwaber notices that the term “Agile” is often used in a careless way.

“Many people think that there are Agile processes. There aren’t. There are processes that conform to the Agile Manifesto principles, such as Scrum and Extreme Programming. However, the word Agile is often used as a description for ‘we aren’t using waterfall.’ That is not what Agile means!”

In Schwaber’s mind, Scrum and Agile started emerging for two reasons:

“The Agile Manifesto was a rallying point for dissatisfaction and a new approach. The emergence of new IDEs that were as powerful as SmallTalk, like VisualStudio and Eclipse, were the tech- nological enablers.”

Downoad the whole article here